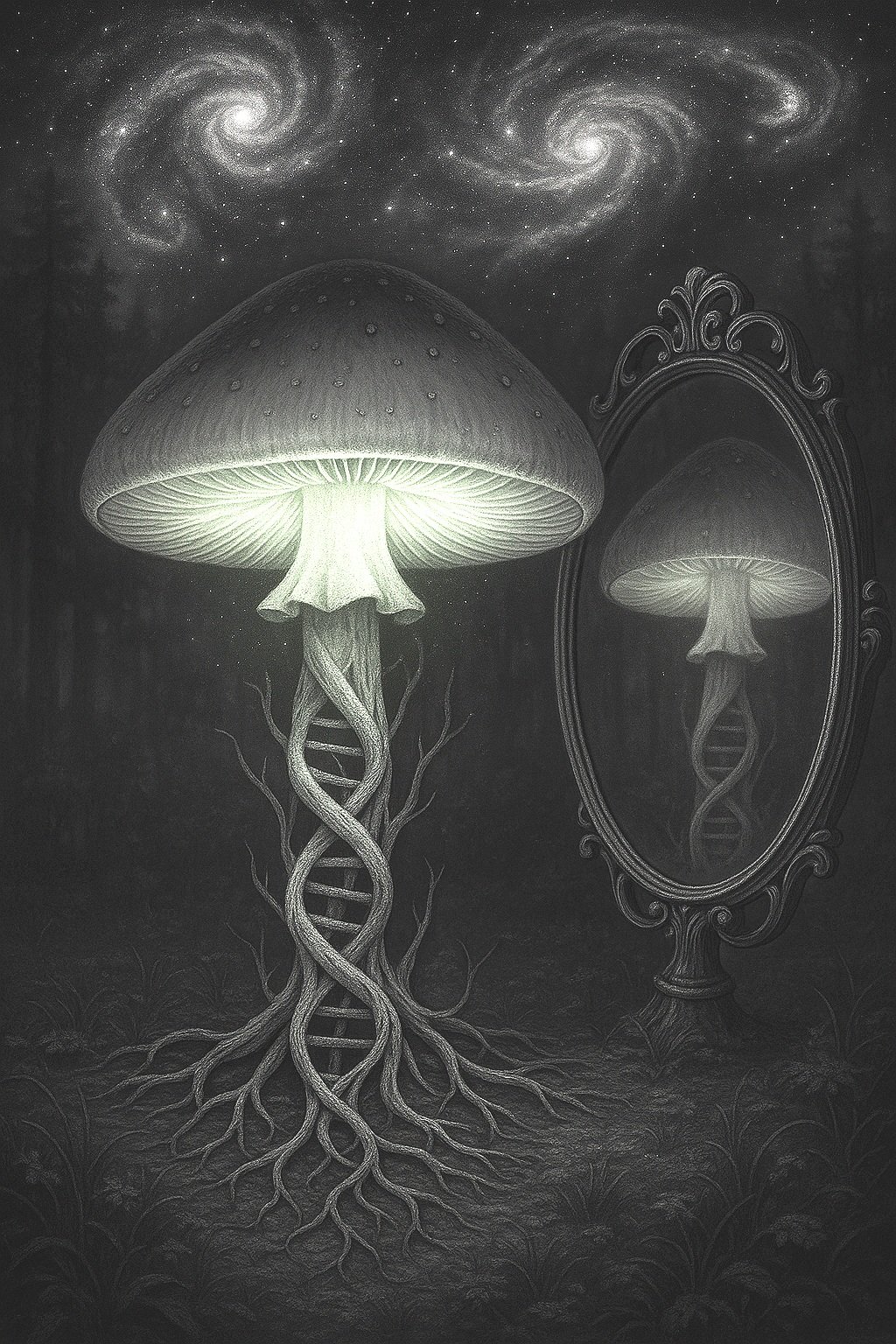

05. Death Cap Mushroom Toxins, Baggage, and Becoming.

Artwork by Galit Shachaf

These days, Australia has been captivated by a tragic mushroom poisoning case. In July 2023, four individuals were diagnosed with death cap mushroom poisoning after attending a lunch where beef wellington was served. Tragically, three of these individuals died, and one survived. Erin Patterson, the hostess of the lunch, is currently on trial for triple murder.

This case blends true crime, culinary arts, the science of mushroom taxonomy, genetic identification, and biochemical characterisation of toxins. It's a gripping narrative that I follow closely, eagerly awaiting daily updates (shout out to the ABC podcast Mushroom Case Daily for their coverage).

Mushrooms are a member of the fungal kingdom. They are fascinating organisms with numerous intriguing traits.

In this post, I want to focus on one particularly relevant aspect: toxin production.

Why Do Fungi Produce Toxins?

The prevailing theory is that fungi produce toxins to protect their spores from predators. These mushrooms disperse their spores into the environment, but if consumed before the spores mature, it can hinder their ability to spread and occupy their ecological niche.

Interestingly, not all fungi employ this defensive strategy. Some fungi take the opposite approach and produce strong attractants to entice predators, facilitating spore dispersal through the predator's excretions.

Truffle mushrooms are a prime example of this strategy, releasing compounds that mimic mammalian pheromones to attract animals that will dig them up, consume them, and spread their spores over wide areas.

Thus, the challenge of spore dispersal can be addressed through two contrasting approaches.

Both mechanisms are evolutionarily sustainable, as evidenced by their presence in nature.

Why Do Some Fungi Choose One Route Over the Other?

Is it genetically determined?

This is a good time to review how the death cap mushroom acquired the ability to produce the toxin.

This is not the result of a slow, linear evolutionary process. Instead, it is the outcome of horizontal gene transfer—a process by which genetic material is acquired from unrelated species. And once delivered, this "genetic baggage" is now a permanent part of the mushroom's genome, conferring both advantages (defence against predators) and disadvantages (metabolic cost, ecological constraints).

Importantly, this baggage is not easily shed. The genes are integrated into the mushroom's DNA, and the machinery to produce toxins is maintained even if the ecological need for such toxins changes.

The death cap is, in a sense, "stuck" with this legacy, which shapes its existence and interactions in the ecosystem.

Does this sound familiar? We all have inherited various baggage that we struggle to shed. We are a product of our genetics, upbringing, environment, etc.

But can we change?

Philosophy: Sartre, Facticity, and Freedom

In existentialist philosophy, especially in the work of Jean-Paul Sartre, facticity refers to all the aspects of our existence that are given and unchangeable: our birthplace, our family, our genetic makeup, our past actions, and the circumstances into which we are thrown. These are the "facts" of our existence that we do not choose and cannot alter.

Yet, Sartre famously asserts that we are “condemned to be free”. Despite our facticity, we are always free to choose our response to our circumstances. Our essence is not fixed by our past or our inheritance; rather, we continuously define ourselves through our actions, choices, and projects.

“Man is condemned to be free; because once thrown into the world, he is responsible for everything he does.” — Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness (1943), Part Four, Chapter One

This creates a tension: we carry the weight of our past, our "baggage," but we are not determined by it. We can reflect on our situation, reinterpret its meaning, and act in ways that transcend our initial conditions.

This is the existential project: to create meaning and identity not in spite of, but through, the burdens we inherit.

The Fungal Metaphor: Inheritance and Possibility

The death cap's story is a vivid metaphor for the human condition as described by existentialists:

Inherited Burdens: Just as the mushroom inherits its toxic genes from an external source, humans inherit traits, histories, traumas, and social conditions they did not choose.

Cost of Inheritance: The mushroom pays a metabolic price for its toxins, just as humans may pay psychological, social, or existential costs for their inherited "baggage."

Not Easily Shed: Both the mushroom and the human cannot simply discard their inheritance. It is woven into their being.

Room for Reflection and Change: While the mushroom's options are limited by biology, evolution shows that lineages can lose or repurpose genes over time—change is possible! Some species of Fusarium fungi have lost their ability to produce harmful trichothecene toxins through evolutionary gene loss, adapting to new ecological niches where the toxin did not offer an advantage. For humans, reflection and conscious choice allow for more rapid forms of transcendence, even if the past is always present.

Conclusion

The death cap's genetic story is not just a tale of evolutionary happenstance; it is a mirror for our own existential journey.

We are shaped by forces beyond our control, but we are not wholly defined by them. Through reflection, choice, and action, we can transcend our inherited burdens and become authors of our own lives.

In the end, both fungus and human are testaments to the interplay of inheritance and possibility, of baggage and becoming.